Preparatory to being the stem cell donor for my upcoming transplant, my brother James traveled to Sacramento recently for an in-person medical examination, an X-ray, some confidential interviews, and yet more blood tests. He came through this day-long process with undiminished enthusiasm, though his travels to countries where malaria is widespread occasioned some concern from the medical team (though he has never actually had the disease himself) and his Canadian address caused two computers to seize up and nearly melt down (which was kind of funny). As I drove him to the airport, he relayed something that one of the many people he had talked to on his visit had told him. She had said, in essence, “You can still back out of this now, no problem. But there will come a point when, if you back out, your brother will die.”

I think he told me this by way of further reassurance, in case I needed it, that he wasn’t going to back out, either now or at any point in the future. I believed him, and still do, but the warning he was given brought me up short. I’d never really considered that particular fact about the stem cell transplant: the radiation and cytoxan I will be getting is so toxic to my immune system that I would not be able to survive at all without another specific person’s stem cells. It makes sense, of course, that one cannot live for long with no immune system whatsoever. The preparatory regimen is in fact designed to wipe my immune system out, as well as to attack any remaining cancer in my body, in order to allow the new immune system to graft more quickly and easily. Still, to hear that, at a certain stage, my life would depend entirely on receiving his stem cells, and his alone, was frightening. All kinds of paranoid, ridiculously selfish questions crossed my mind. What if his plane crashed? What if he were hit by a car on his way in to donate? Nobody else with suitably compatible stem cells would be found in time. Shouldn’t we keep him in a secure location while they administer the otherwise fatal doses of chemicals and/or X-rays to me? Shouldn’t there be a backup donor on call, just in case?

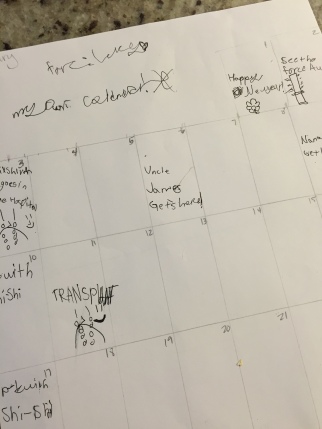

These are the kinds of questions that still occur to me, but they don’t really deserve serious answers. The chances of some tragic mishap befalling him during my window of complete vulnerability are so minute that not even the insurance companies are concerned about them. Still, I can’t help but wonder what it will feel like to reach that point, the point of no return, when my body loses any capacity to defend itself against even a minor infection, let alone cancer. Will I realize what’s going on, or find the emotional energy to care about such an abstract concept? Won’t I be too mired in the daily routine of radiation treatments, chemo infusions, and their side effects, to worry about where my brother is, what risks he might be taking or avoiding, what the statistical probability of his making it to the apheresis machine on January 11 actually is? The odds are so overwhelmingly in my favor, at least on this crucial logistical issue, that I can’t believe I’ll still be worrying about this kind of thing once the transplant process has actually gotten underway.

Behind every wildly irrational fear, however, lurks something much less crazy or foolish: something you might call ignorance, or else, in a different mood, a common-sense refusal to believe in miracles. I think part of what has produced this paranoia in me is my fundamental inability to comprehend or accept the biological, chemical logic of the transplant itself. It all seems like an elaborate, implausible magic trick that they are proposing to play on nature and mortality itself. How can these much-vaunted stem cells possibly live up to their reputation and perform all the tasks they are expected to do? They must inhabit my bloodstream, migrate to my bone marrow, produce millions more of themselves, and build not only a new immune system but a better one, in order to defeat the cancer my own immune system has apparently refused to fight. How far-fetched does that all sound? It sounds like something out of a science-fiction movie. Or out of a witch’s cookbook.

Intellectually, of course, I know that stem cells are a big deal for medical science precisely because they can do all this, and more, but I still don’t really get it. I don’t actually see the products of the astonishing transformations they can effect very often, and though I have met people who have undergone successful allogeneic transplants, they can’t explain how it all actually worked. The dumbed-down things you read in books about transplants don’t make them any more understandable, biologically, and I am insufficiently literate in scientific language to make much sense of more technical explanations. Therefore, I am reduced to a kind of disbelieving wonder when I contemplate the things that are supposed to bring me back safely from that point of no return my brother was warned about. It still feels as if I were going to jump off a cliff in the hope that I will somehow sprout wings and flutter gently to the ground.

Maybe some version of this feeling explains why they call people who have had allogeneic transplants “chimeras.” Not all types of these mythological creatures had wings, but they all look like the product of some unlikely evolutionary quirk or bizarre, unexpected coupling. In other words, they look like crazy shit some starving artist in ancient times dreamed up when he had nothing better to do. Or maybe, if he was really starving, when his whole life depended on it.