Today marks Brad’s 20th day in the hospital, meaning he’s now pushed past his previous hospitalization-length record of 19 days, set back in May. Unfortunately, today has not seen much of an upswing from the discouraging challenges of yesterday. His C. diff continues and is being treated with oral vancomycin; so far, luckily, he doesn’t seem to have the abdominal pain that’s often associated with such an infection.

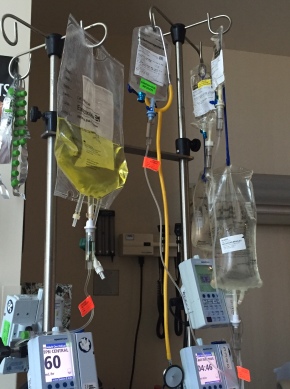

His IV tower is crowded with all his other medications: He’s also on several other broad-spectrum antibiotics (the rest of them all given via IV), the immune suppressant medication he will continue on for several months, TPN (nutrition given via IV; that’s the not-so-delicious-looking yellow fluid), and saline fluid, plus IV acetaminophen when he spikes a fever. For some reason, this last drug—which is just Tylenol, but given intravenously—sends the entire medical staff and pharmacy into a tizzy. Apparently it’s extraordinarily expensive and the hospital pharmacist is strongly opposed to dispensing it. (Surely, however, the cost of the Tylenol is just a drop in the bucket of what this whole hospitalization will cost? It’s hard to fathom how much that might be, and every time I think about it I am grateful for our excellent insurance plan, which comes to us courtesy of the taxpayers of California. Thanks, everyone reading this from in state, and let me just take a moment to acknowledge how privileged we are in this regard and say that I wish everyone in the U.S., and indeed everywhere, had equal access to this level of medical care when they need it.) But Brad can’t swallow pills at all and even liquids are a challenge, so his medical team has been going to bat for him and fighting to get him every dose, to lower his fever. I told the doctor yesterday that if they need someone else to get on the phone and yell at the pharmacist I might have a little aggression to spare these days.

Speaking of fever, it’s been spiking a lot, up to 104ºF last night. That’s sapping his energy, and he’s been dozing most of the time while I have been at the hospital today. His breathing has also been a little more difficult and shallow, probably—according to the doctor—as much in consequence of the fever as of the pneumonia identified on CT.

We were told, well before the transplant, that recovery from it would not be linear, and this week certainly confirms that it has been and will be a roller coaster. I never did like riding roller coasters, and it turns out I like metaphorical ones no better than the nauseating ones in amusement parks. We were all so encouraged, a few days ago, to learn that he was starting to engraft, and it was hard not to think that it would then be a relatively smooth path upward. But we’ve had another sickening drop. It’s equally hard to stay confident that a corresponding rise will come, but it will.